Crossroads for Yucca Mountain

10 December 2008

American officials have recommended that the limit on how much radioactive waste is stored at Yucca Mountain be removed as waste management strategy reaches a crunch point.

|

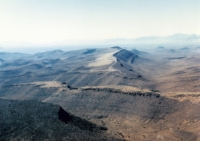

| Yucca Mountain (Image: DoE) |

The limit of 70,000 tonnes of heavy metal only stands until the site for a second waste store is one day selected, but long delays in implementing the overall waste management scheme have necessitated scrapping the limit early.

The change would permit all the wastes from current and planned power reactors, as well as from military activities, to be stored at Yucca Mountain and put off any work on selecting a second storage site for many years. However, any decisions from the advice - and American radioactive waste policies in general - remain to be taken under president-elect Barack Obama's incoming administration.

The process to begin storing used nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive wastes at Yucca Mountain began in 1982 with the Nuclear Waste Policy Act. After the investigation of a number of potential sites across the USA's contiguous states, Congress decided to have Yucca Mountain as the first of two permanent storage sites for used nuclear fuel from nuclear power plants. The Department of Energy (DoE) would take title to the wastes and manage them forever, using a Nuclear Waste Fund built up by a 0.1 cent fee placed on every kWh of nuclear-generated electricity. In 1985 President Ronald Reagan decided that 10% of Yucca Mountain should be used to hold the high-level wastes from military programs.

Under the NWPA, only 70,000 tonnes of heavy metal are allowed to be stored at Yucca Mountain before a second repository site is selected. In yesterday's report, the DoE's Sam Bodman writes that the total amount of material destined for Yucca Mountain currently stands at 58,000 tonnes from the power sector and 12,800 tonnes from the military - already over the self-imposed limit, and increasing at around 2000 tonnes per year.

Meanwhile, the DoE's application to build the repository is with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and it looks unlikely that the store will accept any wastes until after 2018 - some 20 years after originally envisaged by the NWPA. By that time, nearly 90,000 tonnes of material would have built up around the country.

Limited options

The report issued by the DoE yesterday was mandated for about this time by the NWPA as advice to Congress and the President on the need for a second repository. It identified three options for the USA to manage this rather difficult situation of a statutory timeline that has been overtaken by events.

With more than 70,000 tonnes of storage needed, one option is to begin looking for a second site. While many suitable sites certainly exist, it would clearly be a political impossibility to engage positively with potential host communities some ten years before the first site even operates. This would also require new legislation amounting to a new strategy.

Another option is to defer the decision and continue storing power station used fuel on-site. Doing this would incur financial penalties when power plant operators pursue the DoE for the costs of extra and prolonged storage, having already paid for DoE's costs in preparing Yucca Mountain. This is already occurring due to the ongoing delay of over ten years.

The third option, and the one recommended by Bodman, is to simply remove the statutory 70,000 tonne limit on storage at Yucca. The DoE notes that the NWPA does not place any other limits on how much can be stored at Yucca and the physical capacity of the site is far greater.

In the meantime

Another report from the DoE yesterday concerned the proposal that it could take over management of used nuclear fuel stocks from the small number of decommissioned and demolished power reactors. At these sites, the only indication that a nuclear power plant was once there is a row of above-ground dry-storage containers.

The DoE's conclusion was that it did not have the authority to accept the used fuel under present law, and that the action would not reduce costs to the American taxpayer even if it did.

Calculated from a 2020 starting date for Yucca Mountain, the DoE would have to pay up to $11 billion in compensation to the operators of the country's 104 nuclear power reactors for its failure to open Yucca Mountain in 1998. Furthermore, this money would have to come from taxpayers, after rulings that the DoE cannot dip into the Nuclear Waste Fund earmarked for the development of Yucca Mountain.