The finances of Hinkley Point C, and how they still work despite price rises

EDF's latest estimate for building the two EPR units at Hinkley Point C has now reached GBP45 billion (more than USD56 billion) at today’s prices, with startup not being for about another six years. More than a decade since the Hinkley Point C deal between the UK government and EDF was announced in October 2013 - when the plant was expected to come in at GBP16 billion in 2012 prices (equivalent to GBP21.9 billion/USD27.7 billion today) and commence operation in 2023 - both the estimated cost and construction time have doubled.

At its original cost and schedule, the project was criticised by many as an expensive mistake. But even at today’s price tag, a closer look at the numbers shows that the economics of Hinkley Point C still make sense for EDF.

Cost to UK taxpayer

Since the initial terms for the Hinkley Point C (HPC) project were agreed, not much has changed from the point of view of the UK government. The ‘contract for difference’ (CfD) agreement signed in September 2016 was designed to shield the UK taxpayer from picking up the tab for any increase in the construction cost - and so far, this aim has been achieved.

As long as EDF meets certain conditions, the government guarantees a fixed price (referred to as the ‘strike price’) for all the electricity produced by the two 1630 MWe units for 35 years. The strike price was set at GBP92.50 per megawatt hour in 2012 prices; adjusting for inflation, this is around GBP132/MWh (USD167/MWh) in today’s currency values.

At current wholesale prices (GBP69.25/MWh average in December 2023, equivalent to around USD87.30/MWh), this represents a sizeable subsidy courtesy of the UK taxpayer of around GBP60/MWh. At this level, that works out to around GBP1.5 billion per year, based on both units operating at a capacity factor of 90% (ie providing about 25.7 million MWh annually).

On the other hand, whenever the wholesale price exceeds the strike price, HPC’s owners must instead pay the excess amount to the taxpayer. Over the 35-year period when the strike price is in force, such a scenario is far from unlikely: between mid-2021 and April 2023, wholesale prices were at comparable or even higher levels than the strike price, peaking at well over GBP300/MWh and remaining above GBP100/MWh during this period.

The latest construction delay and cost increase do not affect these numbers. Nor do they make any difference to the benefits that the UK receives in return for the project going ahead, for example, the jobs created for around 10,000 workers and 3500 British companies involved in construction. Furthermore, once in operation, the plant will provide around 7% of the country’s electricity, all of which will be associated with close to zero carbon emissions and low power system costs.

Funding the overrun

As things currently stand, it is not the government but EDF that must shoulder the cost overruns. Essentially there are three options available.

Firstly, EDF could take on debt through the bond market. The UK government had originally offered EDF to guarantee GBP2 billion in bonds to finance construction - with the prospect of a further guarantee up to GBP13.1 billion - but EDF did not draw on this facility. Now, after the January 2024 announcement of the increased costs and startup delay, this option could be reconsidered.

The second option is further equity financing by new investors. While there are plenty of organisations that could provide funds in return for an equity stake in HPC, the additional costs may have now precluded the level of return that a private investor would require, at least in the short term.

The last option is to continue using the EDF balance sheet to fund the project. Up to the third quarter of 2023, the construction of HPC was financed by equity from the project’s owners, EDF (66.5%) and China’s CGN (33.5%). Since then, CGN has stopped financing the project, having reached the GBP6 billion investment that was agreed in 2015 - at a time when construction costs were put at GBP18 billion. With EDF now being the only source of project funding, its stake in the project is rising (to 67.7% at the start of this year) as CGN’s share correspondingly decreases.

Even if EDF is able to issue bonds at similar rates to sovereign debt and/or manages to find another equity partner, the company faces a major cashflow headache for the rest of this decade - and that’s without the project costs and schedule overrunning further.

Residual risk

As well as the risk of additional increases in construction cost, there are other risks that could affect the project.

As mentioned earlier, the principal cost to the UK taxpayer is being the counterparty for the strike price. The 35-year period during which the plant operator is guaranteed to receive the strike price for electricity produced at the plant will commence no later than the final day of each reactor’s respective ‘target commissioning window’. If the reactors start up after the end of their target commissioning windows (30 April 2029 for unit 1 and 31 October 2029 for unit 2), then the CfD term will end before the units have operated for 35 years.

It is the first nuclear new-build in the UK for three decades (Image: Alex Hunt/WNN)

EDF has the option of invoking the force majeure clause of the CfD agreement to push back the target commissioning windows, but doing so risks causing a public relations headache that it would probably prefer to avoid.

A far greater risk is termination of the CfD, which could be triggered should unit 1 not be commissioned before the ‘longstop date’. This date was originally 1 November 2033, but was extended by three years, principally on the basis that the COVID-19 pandemic constituted a force majeure. The year 2036 might seem a long way away, but this would mean that the construction duration of unit 1 should not be more than 18 years - a timescale that is not comfortably far off the 16-and-a-half years’ construction period for the EPR in Finland.

The other big risks to the project mainly concern political risk - such as nationalisation of power generation or a nuclear phaseout. The UK government has agreed to underwrite up to GBP22 billion compensation (in 2012 prices, equivalent to GBP31.5 billion today) should any change in policy lead to the shutdown of the plant. As the costs of the project rise, so too does the shortfall in the compensation that might be paid out in such circumstances.

In addition, there are operational risks: although EDF knows how to operate nuclear plants, the expected capacity factor of over 90% cannot be taken for granted: since the start of the decade, EDF’s income has been negatively affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, stress corrosion issues at many of its plants, and regulator-imposed pricing measures. During HPC’s now longer period of construction, along with an expected operating lifetime of at least 60 years, quite a lot can, and occasionally will, go wrong.

Generating income

On the plus side, the amount of electricity that the plant would produce is immense: as noted above, once in full ‘commercial’ operation, it should provide at least 25.7 million MWh annually. At a strike price equivalent to GBP132/MWh (USD167/MWh) in today’s currency terms, this would generate GBP3.4 billion (USD4.3 billion) annual revenue.

From the revenue, operating costs should be accounted for to give an idea of the annual profit. In the June 2017 UK National Audit Office (NAO) report on Hinkley Point C, the expected operating costs (including fuel) were quoted as GBP29.3 billion in 2016 prices over a 60-year operating lifetime. Adjusting for 2024 values, this is equivalent to an annual operating cost of GBP638 million (USD807 million).

Therefore, based on the above figures, annual income (after accounting for operating costs) would be in the region of GBP2.8 billion (USD3.5 billion) at today’s currency values.

The CfD will likely expire in 2064, but the plant would be expected to continue operating into the 2090s, and even into the next century. Seen in this context, even HPC’s vast construction costs are relatively small: a GBP45 billion price tag for an asset that is expected to generate an annual income of well over GBP2 billion for perhaps 80 years or more could be thought of as a sound investment.

The upcoming 2024 edition of World Nuclear Association’s report on Nuclear Power Economics and Structuring explains that the main factor that determines whether a nuclear project would be economically successful is not so much its cost of construction, but the cost of the capital employed to build the plant. The NAO report states that the agreement with the UK government assumed that the investors’ rate of return would be 9.04% (at a time when the construction cost was expected to be GBP18.2 billion in 2016 prices, or GBP23.8 billion/USD30.1 billion today). If this rate of return were applied to the revised construction costs (in today’s currency values), the financing costs alone would require an annual profit of GBP4.0 billion, or nearly 20% more than the total annual revenue (before taking operating costs into account). From this point of view, the project has become an economic failure.

But such calculations ignore the reality of the situation. For any investment, the expected return should reflect the level of risk associated with the investment; in the case of HPC, the 9% cost of finance was set when the project risk was a lot higher than it is today. In the meantime, some of the risks to the project cost and schedule have materialised, but the risk of non-completion has reduced. The question is whether the current level of risk is consistent with the level of return that can now be expected.

Costing HPC

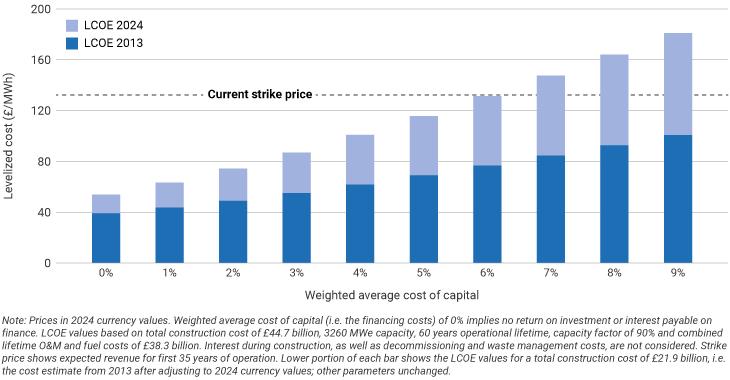

If the lifecycle costs are exactly covered by the plant’s entire revenue, this would imply an average break-even price for every MWh produced by the plant - this figure is referred to as the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE).

Over a 60-year operating lifetime, a 2x1630 MWe power plant with an average capacity factor of 90% would produce 1.54 billion MWh.

The main components of the overall cost of the project are: construction; operations and maintenance (O&M); fuel; and, most importantly, financing. Any charges associated with decommissioning and waste management do not need to be considered: the ‘back-end’ liabilities will be transferred to the UK government at the end of operation and their associated costs are to be met by a fund that would be built up over a period of around 37 years. Given that the fund would not need to be drawn on for perhaps a century and would have been invested in the meantime, back-end costs are negligible.

At today’s prices, HPC’s construction cost is now estimated at around GBP45 billion. The 60-year lifetime operating costs (O&M plus fuel costs) quoted in the NAO report work out to GBP38 billion in 2024 currency values.

If only construction and operating costs (including fuel) were to be covered - and assuming no financing costs - then the LCOE would come to around GBP54/MWh (equivalent to USD68/MWh). This figure can be compared with the current strike price of around GBP132/MWh (USD167/MWh), as well as long-term electricity wholesale prices, which are more relevant during the second half of the 60-year design operating lifetime (ie after the CfD term has expired).

Adding in financing costs raises the LCOE (see Figure). At least for the first half of the plant’s operation, the GBP132/MWh strike price would be sufficient to cover an LCOE with a 6% cost of capital. However, as already noted, it isn’t enough to provide a 9% return on investment, where the LCOE is over GBP180/MWh.

Normally, an equity investor would not accept a 6% return on such a project. However, once built, and with back-end liabilities passing onto the government, the project risk is significantly reduced. At such a time, a return of around 6% over such a long timescale - and, crucially, one that is guaranteed to be inflation-linked for 35 years - might be attractive to an investor.

With the rest of the decade to go before any electricity is generated - and therefore any income is produced - several risks to the project remain. On the financial side, the cost estimates given here may eventually turn out to be quite different from the actual O&M, fuel and even construction costs; and on the construction side, even though much of the risk has now passed, completion by any date - let alone before the longstop date - is never guaranteed. Nevertheless, so long as EDF can successfully negotiate these risks along with the cashflow problems caused by the increased costs, HPC will prove to be a profitable asset for many decades to come.