The UK government is confident "there is a deal to be done" with EDF Energy on Hinkley Point C, but notes that it would not and could not influence the speed at which the utility makes a final investment decision (FID) on the project. "We recognise that the matter now rests with the equity. That's a commercial matter and we have to allow that to play out," said Jeremy Allen, head of procurement and investor relations at the Department of Energy and Climate Change.

Allen spoke at the conference Nuclear Energy's Role in the 21st Century: Addressing the Challenge of Financing that was held in Paris last week. The event was jointly organised by the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency and the International Framework for Nuclear Energy Cooperation.

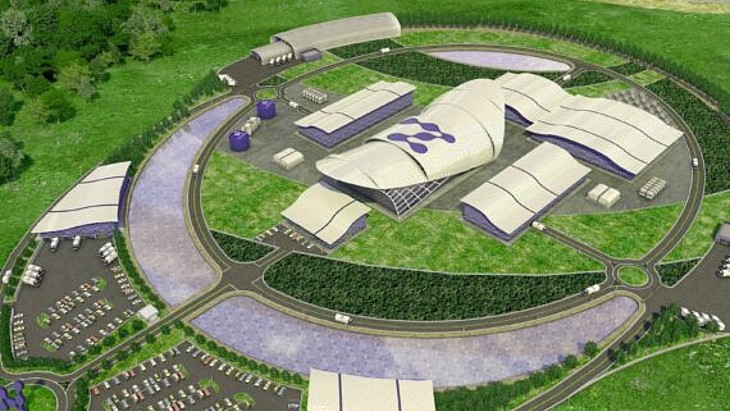

Agreements negotiated by the government and EDF Energy in October 2013 and approved by the European Commission a year later, are for a long-term contract for the electricity generated at the Hinkley plant - two 1600 MWe Areva European Pressurised Reactor units - and for a guarantee for the project's debt. Then, in March this year, the Commission announced its approval of the partnership between EDF and China General Nuclear for the development, construction and operation of three new nuclear power plants in the UK. Under the Strategic Investment Agreement, which was signed last October, CGN agreed to take a 33.5% stake in the Hinkley Point C project in Somerset, as well as jointly develop new nuclear power plants at Sizewell in Suffolk and Bradwell in Essex.

"The agreement with EDF Energy has yet to be signed and we have yet to take a final decision pending the FID the developer needs to take, but this is where we've got to and the terms we put to the European Commission in terms of seeking state aid clearance for the deal," Allen told delegates.

Asked whether the government could have put a deadline on the FID, which EDF Energy had been expected to make at the end of last year, Allen told World Nuclear News: "We think it's in the interests of EDF and its partners to move to FID when they can, but they are clearly having processes and issues that they need to deal with. We look forward to returning to the table when they've done that. We remain confident that there's a deal to be done, but we'll take our final decision when that FID has been taken."

A key element of the agreement between EDF Energy and the government is the Contract for Difference (CfD), which Allen noted is a private law contract between a low-carbon electricity generator and the Low Carbon Contracts Company, which is government owned.

The generator is paid the difference between the 'strike price' - a price for electricity reflecting the cost of investing in a particular low-carbon technology - and the 'reference price' - a measure of the average UK market price for electricity. The CfD enables greater certainty and stability of revenues to electricity generators by reducing their exposure to volatile wholesale prices, whilst protecting consumers from paying for higher support costs when electricity prices are high.

"As with any other contract, it has dispute mechanisms to allow arbitration and resolution. But it's a protection for those who need long-term stability that the contract they have and the assumptions they [make] are going to be protected," Allen told the conference. "By using this mechanism we have found we can drive competition effectively. We are already auctioning CfDs in renewables, allowing real price competition to drive down the cost to the consumer. With nuclear, we didn’t have that ability - at the time when we began this process, there was only one viable nuclear project and that was EDF's plant at Hinkley, which was sufficiently mature to allow us to enter into a series of negotiations. So we did a bilateral negotiation and we're happy with that because we feel we've negotiated a good deal for the consumer. Over the very long term, who knows though; can competition come into the allocation of nuclear CfDs? That would be a very different thing, but we will always look at how to get the best deal for the consumer."

The strike price is determined by competitive bidding for renewables or through bilateral negotiation for nuclear. The reference price is a measure of the average market price - day ahead for renewables and season ahead for baseload generation.

The CfD for Hinkley Point C includes a strike price of £92.50/MWh, falling to £89.50/MWh if a FID is taken on Sizewell C. It has a payment duration of 35 years from the point at which each reactor at Hinkley becomes commercially operational or the last day of the target commissioning window for that reactor, whichever is earlier.

"The need we thought about several years ago, for a very substantial guarantee to underwrite debt, has lessened because of the way that EDF is now choosing to finance Hinkley,” Allen said. "There is an offer from government to provide a portion of debt underwriting for round about £2 billion if it’s required, if the developer wants to draw it down, that is going to be available."

Part of a package

Allen stressed that the CfD needs to be seen "as part of a package" that reflects some of the unique features of new nuclear. "There's also a side agreement between the Secretary of State [for Energy and Climate Change] and the investors which, if the deal goes ahead, will be signed," he said, referring to the political risk agreement that sits outside the terms of the contract. This is a direct agreement between the Secretary of State and the developer as investors, "recognising that nuclear above all other generating technologies is susceptible to political intervention and the need to do something about that risk is critical," he said.

The political risk agreement offers compensation "in the event of a political shut down", other than for certain reasons including health, nuclear safety, security, environmental, nuclear transport or nuclear safeguards.

"This is where a future government in the UK decides for political reasons that it does not want nuclear in the system, which at the time might be a valid and reasonable decision to take, but we need to offer some protection to the developer who has obviously sunk huge amounts of capital to build that asset and that needs to be remunerated in some way. So the political risk factor is there to say nuclear, probably alone and above all generating technologies, needs that additional protection."

It will not cover, however, a plant being shut down "because it is not safe or it is not consistent with the regulatory regime". Allen said: "It's not a free pass; it's purely whether on an arbitrary political basis the government of the day says we don't want nuclear on the system."

The negotiations with EDF Energy have also included change in law arrangements, according to which compensation could be paid or received in relation to certain future legislative amendments - including in respect of specific tax clearances, and uranium and generation taxes. "We are prepared through the contract to offer compensation where there are changes in law that affect the economics of the plant when those changes are unforeseeable, material and specific to or discriminatory to the technology or the individual asset," Allen said. This protection excludes some changes in the law, such as those designed to improve efficiency or lead to increased safety, but provides "risk protection for things that the developer can't manage where those may arise", he said.

One of the key challenges when the government and EDF Energy started their negotiations on the Hinkley deal was, Allen said, "the inability of either side to know what would be going on in 15, 20, 30 years with that asset".

"The choice we had was either asking the developer to price in those factors now or taking a flexible and pragmatic approach, which is to reopen the deal when you know what those factors are - be they fuel costs, or other issues that might affect the economics of running the plant," he said. "How do we take a view of what's likely to happen in 2040? We'd be asking the developer to take a view and to bring it forward into today's money. That didn't seem the right way to us, so in terms of an operational plant we are building in what we call the 'opex reopener'."

This will allow for the adjustment of the strike price upwards but potentially downwards in favour of the consumer in relation to certain operational and other costs. This will be done at two fixed points - 15 years after commissioning and 25 years after. "We think that's a realistic and pragmatic way of managing those uncertainties over such a long-dated asset," Allen said.

The government has also introduced a cost of construction gain share mechanism to incentivise the developer to "outperform on the construction". Savings made on the construction of Hinkley Point C would be shared - a 50% share up to a certain level or 75% share over a certain level.

"This basically allows a greater return if they outperform, but offers then something back to the consumer in terms of a lower strike price," Allen said. "If the developer outperforms, say by £1 billion, that will be shared 50-50; if it's greater than that, the majority will come to the consumer of that benefit." He stressed that this element of the agreements "is a gain share, not a pain share" because "we're not taking construction risk on behalf of the consumer".

The Hinkley deal also contains equity gain share, which means that project outperformance or equity sales that increase the investors' realised equity returns above the base case would be shared. Equity gain share extends beyond the 35-year term of the CfD to the lifetime of the asset.

This "reflects the fact that as you build to time and budget we want that benefit to be shared with the consumer," Allen said.

"There are other things we're doing around tax," he said. "Business rates that apply now, what will they be at the point of commissioning? We'll look at that and may reopen the strike price. Similarly transmission charges - we don't know what they'll be at the point of commissioning, so again we may look at the strike price."

He added: "We’re offering some protection where output of the plant is curtailed because the way that we compensate curtailment now has changed significantly to the detriment of a plant like that. It is not about guaranteeing offtake. But it is saying that, if the regulatory regime in the 2020s or 2030s is so markedly different in how we compensate curtailment today, we will look at offering protection through the contract."

Decommissioning fund

The agreements also take in account the management of waste and the decommissioning of the Hinkley plant. The UK has "a legacy in nuclear and needs taxpayer's support for decommissioning and the treatment of waste created in the 1950s and 1960s", he said. "We're not going to do that again. It must be dealt with by the developer, although the cost will be transferred through the contract to the consumer. And we think that for Hinkley that will be about £2/MWh of the overall price."

This funded decommissioning program (FDP) is based on the Energy Act 2008 that requires all new nuclear operators to meet their full decommissioning costs and be responsible for their full share of waste management and disposal costs, so that the taxpayer will not bear the burden in future. An FDP must be approved by the Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change.

Allen said: "It is the operator's duty to set aside funds for waste and decommissioning costs from the start of generation and nuclear-related construction cannot begin without an approved FDP in place. The operator is expected to enter into a waste transfer contract with the government, which sets out the terms under which government will take title to and liability for the plant's used fuel and intermediate level waste for a fee."

Overall, the package of agreements aim for "effective and sensible risk allocation between the parties", he said.

"Taking away risks that the developer cannot manage and cannot price, like a political shut down event or tax changes that would materially affect the economics, we can do something about that in a sensible way by allocating that risk away, but leaving the risks that are appropriate to the developer within the contract. And that's true whether it's renewables or nuclear or any other technology.

“But it's clear that through the CfD, we believe this is a good deal for the consumer. We're prepared to take some risk, but not construction risk because that doesn't seem to us to be appropriate when the taxpayer is least able to manage that. And whilst we want to reflect the issue around dispatch certainty and give some confidence there, the idea you’re putting the consumer on the hook through an offtake agreement would seem a step too far for us. So there are limits to this even where we think there are greater opportunities through the CfD to share risk appropriately."

Researched and written

by World Nuclear News