Global temperature increase can be limited to 2°C by 2100 without harming economic growth, but the world will miss the target if it does not act fast to limit carbon emissions from fossil fuels, according to a special report from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Speaking at the launch of Redrawing the Energy-Climate Map, a special report prepared by the IEA's Directorate of Global Energy Economics (GEE), IEA executive director Maria van der Hoeven said that the world is currently on a path which is likely to result in a temperature increase of 3.6-5.3°C by 2100 - far in excess of the 2°C recommended by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). However, the IEA maintains that this can still be achieved in the short term without jeopardising economic growth.

Redrawing the Energy-Climate Map recommends four key policy measures to stop the growth in global energy-related emissions at no net economic cost in its 4-for-2°C scenario: improving energy efficiency; limiting the construction and use of the world's least-efficient coal-fired power plants, minimising atmospheric methane emissions from upstream oil and gas production, and accelerating the partial phase-out of fossil fuel consumption subsidies.

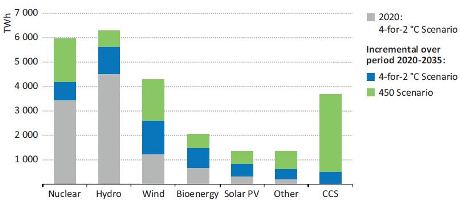

|

| World electricity generation from low-carbon technologies by scenario (Image: IEA) |

The long lead-time for nuclear projects means that extra nuclear plants do not figure beyond already recognised plans for new capacity in the actions to 2020. However, nuclear remains a vital underpinning technology in the IEA's so-called 450 scenario, which seeks to limit final temperature increase to 2°C. This sees nuclear generation increasing by almost 1800 TWh in 2035 (or about 40%) over the level achieved in the 4-for-2°C scenario. Under a 2°C trajectory, the report notes, net revenues for existing nuclear and renewables-based power plants would be boosted by $1.8 trillion (in 2011 dollars) through to 2035, while the revenues from existing coal-fired plants would decline by a similar level.

Meanwhile, the report says, the energy sector must prepare itself for the physical impacts of climate change. It must build in resilience to sudden and destructive impacts arising from extreme weather events and also to more gradual impacts such as changing average temperatures, sea level changes and shifting weather patterns. The report calls on industry to be proactive in assessing risks and impacts as part of its investment decisions or risk finding itself in the position of having to carry out expensive retrofitting or even early retirement, especially of more carbon-intensive assets.

Putting off such a move could be costly for the energy sector, the IEA report claims. Delaying such actions until 2020 - the earliest date at which an internationally negotiated and binding agreement on emissions limitations through the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) would be likely to come into force - would result in substantially increased costs as the world would effectively have become more "locked in" to carbon-intensive capacity in the meantime. "Delaying stronger climate action until 2020 would avoid $1.5 trillion in low-carbon investments up to that point, but an additional $5 trillion would then need to be invested through to 2035 to get back on track," the report notes.

"The question is not whether we can afford the necessary investments given the current economic climate. The fact is we simply cannot afford to delay," van der Hoeven concluded.

Researched and written

by World Nuclear News

_97013.jpg)