The shelter at-a-glance

Chernobyl unit 4 was destroyed in the April 1986 accident (you can read more about it in the World Nuclear Association's Chernobyl Accident information paper) with a shelter constructed in a matter of months to encase the damaged unit, which allowed the other units at the plant to continue operating. It still contains the molten core of the reactor and an estimated 200 tonnes of highly radioactive material.

However it was not designed for the very long-term, and so the New Safe Confinement - the largest moveable land-based structure ever built - was constructed to cover a much larger area including the original shelter. The New Safe Confinement has a span of 257 metres, a length of 162 metres, a height of 108 metres and a total weight of 36,000 tonnes and was designed for a lifetime of about 100 years. It was built nearby in two halves which were moved on specially constructed rail tracks to the current position, where it was completed in 2019.

It has two layers of internal and external cladding around the main steel structure - about 12 metres apart - with both breached in the drone incident. The NSC was designed to allow for the eventual dismantling of the ageing makeshift shelter from 1986 and the management and containment of radioactive waste. It is also designed to withstand temperatures ranging from -43°C to +45°C, a class-three tornado, and an earthquake with a magnitude of 6 on the Richter scale but, as the meeting heard, it was not designed to withstand missile or drone strikes.

The damage

On the morning of Valentine's Day in February a drone struck the New Safe Confinement shelter, with security cameras catching the explosion that took place on impact.

Maksym Protsenko, head of the engineering centre at Chernobyl nuclear power plant, said that before the drone damage, the next steps which had been being planned for the NSC was designing, procuring and then dismantling the original - now unstable - 1986 shelter and "the development of technologies for and retrieval of fuel-containing materials and long-lived radioactive waste" from the original shelter, "followed by their conditioning, storage and final disposal".

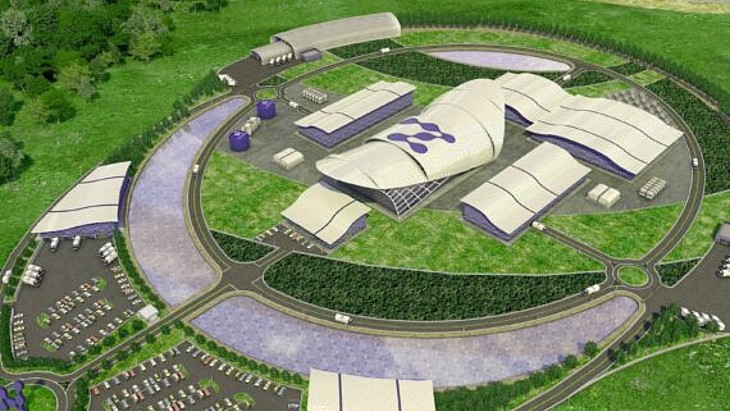

The original shelter is now within the New Safe Confinement (Image: CHNPP)

These had all had to be put on hold and he outlined the scale of the damage - with the impact site seeing "pass-through damage to an area of 15 square metres"; damage to cladding from the fires that smouldered afterwards in an area of about 200 square metres; technological equipment - including the power supply system, ventilation and control systems - damaged by "drone fragments and blast wave"; the membrane, designed to help ensure the tightness of the shelter to protect the external environment, smouldered and more than 340 holes had to be cut in the shelter to allow firefighters to put out the fires. There was also damage to the steel structures of the arch and crane systems.

The IAEA's Martin Gajdos, Technical Coordinator of the Department of Nuclear Safety and Security, said that the damage meant the New Safe Confinement "is currently unable to to perform its confinement function", although he stressed that there had been no change in measured radiation levels compared with prior to the drone strike.

The planned repairs

Protsenko said that inspections and assessments had been taking place with the aim of drawing up estimates for a repair plan, but this would take time and so there was therefore a need to go ahead with temporary repairs to protect the structure from further weather-related damage.

Steven White, from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, said that its long-running support and work at Chernobyl was now focused on the urgent need for repairs to the New Safe Confinement. He said repair costs were estimated to exceed EUR100 million (USD118 million).

He described the extent of the damage as "severe and complex" and warned that "full restoration under original design was unlikely ... difficult choices lie ahead". He thanked the financial contributions in the past few months from the European Union, France and the UK and appealed to the international community to continue its support, saying Chernobyl "remains one of the world's most fragile nuclear facilities".

Oleg Korikov, Director General of the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine, said that between 2005 and 2008 emergency stabilisation measures had been put in place for the original shelter to decrease "the risk of the shelter collapse and potential large release of radioactive dust to the atmosphere". They were intended to last for up to 15 years and allow for dismantling to take place once the New Safe Confinement was in place and commissioned, by 2023. However, he said, that has not happened and with the current state of the New Safe Confinement "planned measures for the Shelter Object unstable structures dismantling are impossible".

Korikov hosted the event at the IAEA's headquarters in Austria (Image: WNN)

The New Safe Confinement was financed via the Chernobyl Shelter Fund which was run by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. It received EUR1.6 billion from 45 donor countries and the EBRD provided EUR480 million of its own resources.